Pravasan Pillay was born in 1978 in Durban. He has published a chapbook of poetry, Glumlazi (2009), and a collection of comedic short stories, Shaggy (2011), co-written with Anton Krueger. Pillay's poetry and short stories have appeared in numerous books and journals and on websites. His short story 'Mr Essop' appears in The Edge of Things, an anthology of South African short fiction published by Dye Hard Press. His humour pieces have appeared in A Look Away Magazine, Mail & Guardian and McSweeney's. He is the editor and co-founder of the small press Tearoom Books. Pillay has worked as a freelance journalist, philosophy lecturer, production and project manager, and copy editor. He currently lives in Sweden and works as the international editor of a Swedish trade magazine.

DH: Your short story ‘Mr Essop’, in The Edge of Things, focuses on a child growing up in Chatsworth, Durban, where you also come from. It makes me curious about your background and how you came to writing.

PP:I come from a single-parent working-class family. Both my parents read a lot and I was encouraged to do the same, so I got through many of the classics at an early age, as well as lots of genre and contemporary fiction. Apart from books, I read superhero, horror, fantasy, sci-fi and war comics, and humour magazines such as Mad. Unlike many parents, mine didn't discourage me from reading comic books. I don't think they made a distinction between high-brow and low-brow culture, which is something I inherited from them. My parents divorced when I was quite young and my mother, brother and I moved around a lot, and that meant having to transfer schools a few times. I think the combination of being quite lonely at each of these schools – which is something I didn't mind too much – and my appetite for reading probably led me to writing. I began writing jokes, stories and plays around the age of 10 or 11.

To what degree has your background influenced your writing? You have said that you dislike being labelled an ‘Indian writer’.

I can understand why I might be labelled as an Indian writer. My short fiction is all set in a little corner of the Indian township of Chatsworth, which is the place I know and can write about best, and the characters are all Indian – so there's certainly legitimate grounds for my race to be highlighted. However, I'd like to think that what I'm trying to do in the stories, technically and thematically, is a bit more universal.

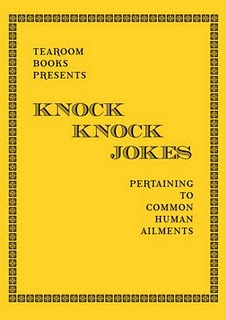

You have worked in various creative forms – short fiction, poetry, film and music – and one common thread among them is humour. I am thinking specifically of the Knock Knock Jokes pamphlet you published through Tearoom Books and your most recent book, Shaggy (BK Publishing). I sometimes get the feeling that humorous writing is frowned upon in SA, that it is not considered ‘serious’. Do you think that South Africans, considering our history, are a bit too obsessed with tackling ‘serious’ topics? There are also many different approaches to humour – it is a bit of a loose term. Do you have any singular approach?

You have worked in various creative forms – short fiction, poetry, film and music – and one common thread among them is humour. I am thinking specifically of the Knock Knock Jokes pamphlet you published through Tearoom Books and your most recent book, Shaggy (BK Publishing). I sometimes get the feeling that humorous writing is frowned upon in SA, that it is not considered ‘serious’. Do you think that South Africans, considering our history, are a bit too obsessed with tackling ‘serious’ topics? There are also many different approaches to humour – it is a bit of a loose term. Do you have any singular approach?You're right, there are many different kinds of humour; and it’s important for a writer to know what kind of laugh he or she is aiming for. I suppose my own approach to humour tends towards the sarcastic and ironic. The late Robert Kirby said: ‘You can’t have humour without offending somebody. Every joke offends somebody down the line. Humour that didn’t plunge the knife into somebody’s ribs would be terribly pale, vapid, weak.’ I concur.

You published a small collection of short poems, Glumlazi, as Tearoom Books’ first title. Some of the poems are only two lines long, almost like haiku or text messages. Do you think that brevity is often more powerful than longer, ‘more developed' poems? Sometimes it seems to me that very short poems can act almost like a punch in the face or a wisecrack.

I'm not sure if shorter poems are more powerful or not, but they're what I prefer reading and writing. I like your use of the word ‘wisecrack’ because I think that's a more accurate classification of the contents of Glumlazi. It was a mistake to label it as poetry. I think that the brevity of the pieces and the inauthenticity of the emotions expressed in them are a reaction to the earnestness and clichéd register of ‘more developed poems’ that you mention. In a way, what I was trying to do was a kind of anti-poetry.

You started Tearoom Books a few years back, with your wife Jenny. Tell us more about it. There is also the Tearoom Books blog, which posts daily. It’s not just a promotional online presence for your press, but an online publication in itself.

Tearoom Books is the natural development of my interest in zines, hand-made books and micro publishing. I've always micro published in one way or the other. While I was at high school I wrote and distributed comic books and co-wrote a satirical weekly handwritten newsletter, and at university I edited and distributed a photocopied zine. I started Tearoom Books because I wanted to publish Glumlazi and I was pretty sure that no else would. Our aim at Tearoom is to publish well-designed chapbooks and pamphlets of contemporary poetry, fiction and humour. We're happy to keep it very small scale, perhaps a chapbook a year.

The blog publishes new content from writers that I enjoy. To an outsider, the site can appear a bit incoherent ‒ that's a consequence of trying to achieve a tone rather than a unifying theme.

Tearoom Books recently published its first e-book, the anthology of poems and recipes called Reader Digest. Is the shift to e-books likely to be permanent?

I prefer print to the screen. Reader Digest was published as an e-book purely because I didn't have the money to print it. It's been relatively successful receiving close to 1000 reads, which we would have never achieved with a regular chapbook – so that's something to keep in mind for future publications. But if we have the financial resources, I still see us doing hard copies.

You have also made some short films, and with Jenny formed a folk music duo called The Litchis. Tell us more about that. Which filmmakers and musicians/bands do you like?

The films are amateur, essentially home movies with credits appended on them. Last year we shot a more professional – at least by our standards – effort and hopefully we'll get it edited some time this year.

The Litchis was started as an archival project with the aim of translating the sugar-cane plantation stories of the late folklorist Sivakami Chetty into a folk music idiom. We later encompassed a few other folk stories, such as Rachel de Beer.

I watch a lot films and have a particular interest in b-movies and exploitation cinema. I think that there's very compelling art to be found in these genres. Most people watch these types of films in quite a condescending, ironic way – which I think is a shame. There's a quote which I recently came across in the comment section of an exploitation film site which summarises my attitude well: ‘Films like [these] are folk art...like the works of Grandma Moses or Henry Darger. Their failures of perspective, anatomy or narrative logic are excused when they achieve effects that go beyond the conventional. Because movies are seen as a narrative art, naive works like [these] don't get the same sort of consideration that other forms of folk art receive.’ I think that if you consider b-movies in this manner, as folk expressions or folk art, then a different type of interpretation and appreciation becomes possible. Because these films are made by amateurs or people on extreme fringes of the established movie system, their contents and structures are very often free of the clichés found in mainstream and even art house or indie cinema.

I don't read comics as much as I used to, but when I did it was the stories above all that drew me in – which is the same thing that I look for in prose. Having said that, there are things that you can do with images and text that can't be done as well in prose or film. For instance, look at Alan Moore's graphic novels From Hell or Watchmen, which are two of my favourite books. The structure and the complexity of the plots and references in these works could never be done as well in other mediums, which is why the film adaptations were so bad.

In collaboration with Anton Krueger, you have just published Shaggy, a collection of humorous monologues. How did the collaboration work? Brion Gysin wrote that when there is a bringing together of two minds, there is the creation of a third mind, which, as I understand Gysin, almost starts operating as an independent entity. What is your opinion on that?

Writing with Anton is probably one of the most enjoyable creative experiences I've had. He is remarkably generous both as a collaborator and a person. We have different approaches to humour: Anton is more in-the-moment and favours the absurd while I'm more structured and grounded in the everyday. His humour is also more humanistic while I tend towards meaner, more offensive comedy. I think that either extreme on its own wouldn't work, but by combining our sensibilities we temper each other and the result is a more well-rounded comedy.

Writing with Anton is probably one of the most enjoyable creative experiences I've had. He is remarkably generous both as a collaborator and a person. We have different approaches to humour: Anton is more in-the-moment and favours the absurd while I'm more structured and grounded in the everyday. His humour is also more humanistic while I tend towards meaner, more offensive comedy. I think that either extreme on its own wouldn't work, but by combining our sensibilities we temper each other and the result is a more well-rounded comedy.

The book arose by accident. Anton and I had originally planned to write one story together, and it was meant to be a serious genre piece. We attempted a few more of these but we found it impossible to not insert jokes into them, always at very serious moments. That's when we decided to abandon genre stories and write straight-up comedy. We write a story by first batting around a few conceits until we can both agree on one, then we create a shared online document which we both work on simultaneously. The first draft gets written quite quickly, in about a day or two, then we put it aside for editing at a later date. Even after we'd written quite a few of the stories, we still didn't have any concrete publishing plans in mind. Our sole aim was to make the other person laugh.

I would agree with Gysin's observation. The writing in Shaggy definitely comes from a 'third mind.' Reading through the manuscript it was very difficult to remember which one of us came up with a particular joke.

Any other comments?

Who gives the shower head?